Complexity ‘Can’ Be Planned For

Just because ‘you’ learned about it today doesn’t mean it’s never been done before.

In a recent post on LinkedIn re: the James Webb Space Telescope I made the comment that it had been completed through “meticulously planning how the emergent practices would be applied.” This was in part to highlight that the idea that project mgmt has *always* been a ‘hybrid’ construct, and the co-existence of complexity, flexibility, and constraints isn’t really ‘new’.

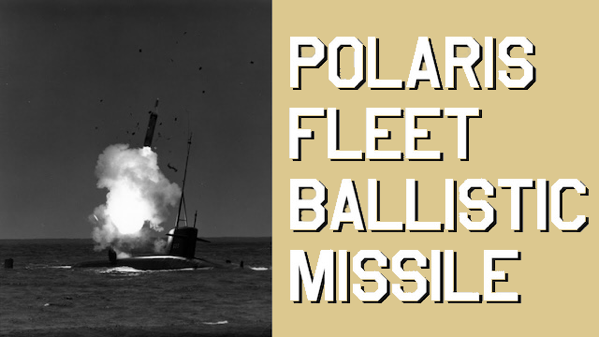

Skimming through the Sapolsky book on the Polaris missile program recently I ran across the following that, in part, explains its success, and reinforces my comment.

See if you can identify the following concepts – empirical data for decision-making, an iterative development approach, technical and logistical complexity, physical limitations, the presence of an MVP, a backlog, feature selection based on ‘value’, the triple constraints, and most importantly, the known and unknown and the planned and unplanned all existing in the same place, to achieve the same goal.

I also really like the term ‘disciplined flexibility’.

“The FMB [Fleet Ballistic Missile] development problem centered on the uncertainties of the system integration. Whereas progress in each of the component subsystems could be generally anticipated, it was difficult to predict far in advance the moment of effective synchronization for all subsystems. The development team’s approach to this problem involved the application of a number of related policies that might be summarized as disciplined flexibility. The only dimensions that were permitted to be fixed at the beginning of the development were those forced by the requirements of submarine construction, the basic physical boundaries of the system. Within the systems physical constraints, all performance options were kept open to allow for the collection of sufficient information upon which to base decisions. There were in each subsystem backup (parallel) developments and fallback (minimum acceptable performance) positions. Having control over the systems military requirements, FMB developers could, with the advent of accelerated schedules, select values for subsystem performance that the development data indicated would add up to a viable and achievable weapon system. All further subsystem advances were saved for consideration in the next version of the system. The existence of a planned series of system improvements – A-2 and A-3 and the various submarine classes – was important for it meant that the development team was relatively free from the normal pressures to make a given system perfect, the kind of pressures which drive up program costs and lead to significant schedule slippages. The development effort’s discipline therefore was in the physical constraints of the submarine and in the determination to meet accelerated schedules; its flexibility was in avoiding the premature commitment to any particular performance goal.”

– Sapolsky, H (1972) The Polaris System Development, p. 250

Now what’s really important to note is that this program took place between 1956-1960.

This means the program was ‘completed’ 9 years before the founding of #PMI, 10 years before Royce’s (much maligned) Waterfall paper, 36 years before the first edition of the PMBOK Guide, and 41 years before the Agile Manifesto was written.

So I think it’s pretty safe to say that project mgmt has *always* been able to merge both the predictive and adaptive needs of a project.

Originally published on LinkedIn

March, 2025